The Volunteers, pigment-medecine Anne Le Troter

18 February — 23 April 2022

In this exhibition, Anne Le Troter continues her exploration of the mechanisms of language and the power of speech through sound, writing and installation. Laureate of the 2021 ADAGP grant dedicated to the Marc Vaux Archive, she approaches the thousands of photographic plates as a huge sound archive populated by the voices of artists. From 1920 to 1970, Marc Vaux documented the Paris art world, photographing artists and models, works of art, exhibits, salons, artists’ workshops, galleries, cafés, balls, parties as well as a great number of administrative documents. With nearly 130,000 photographs, the collection held at the Pompidou Centre’s Kandinsky Library offers an image of the Parisian art scene as a hybrid and transnational centre of creation. It bears witness to a day-to-day reality fed by individual and collective histories; widely divergent from the narrative of a homogenous modernity collected around a few heroic figures.

Of the five thousand artists represented, Anne Le Troter is interested in the more anonymous figures, activists and federators; such as Marie Vassilieff, who opened a “popular canteen for artists and models” in 1914, Louise Hervieu, who founded an “association to establish the health booklet” in 1937, and Marc Vaux himself, who hosted a “mutual aid centre for artists and intellectuals” in 1946. Inspired by the detours of the lives of artists involved in care, Anne Le Troter composed a sound play in which she gives voice to polyactive artists, caregivers or patients, art therapists, models, nurses, paramedics, resistance fighters. Sounding their words in the interstices of mute images, she composed conversations among them about their health, their work-related illnesses, their mobilizations, the material conditions of their lives … To do so, she invited living art workers – Victoire Le Bars, Ségolène Thuillart, Simon Nicaise, Nour Awada, Agathe Boulanger, Martin Bakero, Romain Grateau, Emmanuel Simon, Eva Barto and Juliette Mailhé – to lend their voices and talk to the “not-dead” artists of the Marc Vaux collection – Suzanne Duchamp, Henri-Georges Adam, Marie Vassilieff, Max Beckmann, Joy Ungerer, Jean Cocteau, Anne Chapelle, Bessie Davidson, Madeleine Dumas, Ossip Zadkine, Claudette Bergougnoux, Kiki de Montparnasse, Paul Éluard, Joséphine Baker… The various protagonists of this sound piece navigate through the fragments of a French history of art and of healthcare policies for artists; they observe both their affiliation with the general social security system and their social insecurity (no maternity leave, nor leave for work-related illness or injury); they recount the struggles of art workers, retrace the advent of the health booklet, listen to the gaffes of old age insurance, and allow themselves to be guided by mutual aid, pigment and medicine. Through their conversations, the people who Anne Le Troter calls “the volunteers” compose a new trans-historic identity. Together, they develop a medical autobiography of a hybrid collective body.

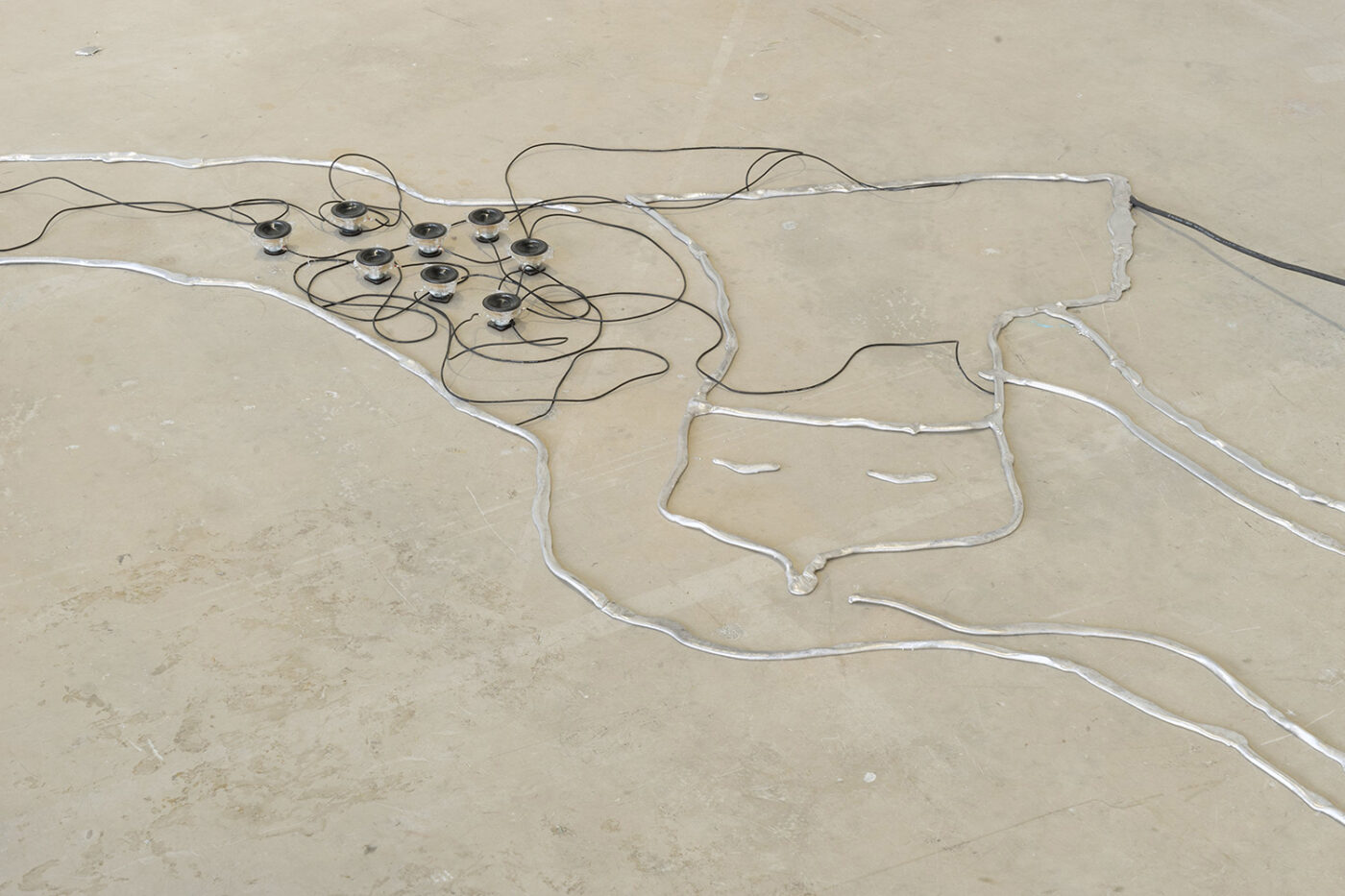

At Bétonsalon, this polyphonic narrative coils itself into the art centre: voices run along fragile metallic ramifications cropping out of flaws in the floor; networks of audio cables cascade softly from the ceiling to connect with tiny, shell-less speakers and come to caress a sound floor; breathing and bodily fluids make the glass surfaces vibrate. This exposed sound mechanics is incarnated in the material of the space as though by a vast, amplified, carnal envelope. The sound conductivity is everywhere fragile, requiring particular attention, from the feet to the ears. As you listen, words mingle with the noises of this reconstructed collective body and the ambient sounds adhere to the words. These two sources of sound might appear to be opposite – one discursive, the other noisy – but by listening attentively, we see that they change through contact with each other; the meaning blurs and the noise takes on meaning.

Primordial Soup Tiphaine Calmettes

20 May — 23 July 2022

Tiphaine Calmettes creates a new series of sculptures that allow you to sit down to taste a drop of kombucha, drink a flower tea kept warm in a gargoyle’s stomach, help yourself to broth from a hollow amidst bread crusts, smell the warm redolence of all this cuisine, follow trickles of water as they dribble out of a monster’s mouth, observe ochre light filtered through a dried kombucha starter, feel the earthy cavities of the surfaces around….

These sculptures are assemblages of previous experiences, works or rejects that have not completed their metamorphosis: under their own inertia and due to wear and tear, some materials give way under their own weight, or seep, crack or evaporate as they are sensitive to heat. All of them are doomed to be further transformed after the exhibition. Whether shaped by skilful hands or left in their initial state, they undergo involuntary transformations on their own. These versatile shapes have not only ingested the various strata of the artist’s work, they have also experienced motifs from distant periods–anthropomorphic utensils, stony plants, animals with pouring lips… –an entire monstrous bestiary drawn from a sort of imaginary natural history.

“Primordial soup” is a term associated with a scientific theory that says that life on Earth is the result of spontaneous generation within a milieu warm and sticky enough to allow life to arise. A whole ecosystem sustains itself in this primordial soup. These sensory sculptures that seem to have emerged from a troglodyte kitchen, turn Bétonsalon into an inhabitable place. Thanks to them, Bétonsalon settles into a sort of telluric domesticity.

Off-site / Cayenne julien quentel

Exposition à Pauline Perplexe

10 June — 11 July 2022

10 June — 11 July 2022

“I would like not to lock this exhibition into any kind of mood through my words. I hate it, these exhibition texts full of emotions, which overplay with great effect what should be played out elsewhere. I hate it almost as much as I hate it when people tell me what to see, or rather, what to understand through what I see – as if that were the question, or the issue, in short, the goal.

So we can stick to a few stable pieces of information: the exhibition is called Cayenne: it’s the name of the garage owner’s dog, right next to the house. It is also the name of a city, a luxury car and a pepper. Four sculptures of different nature and scale are installed there. They don’t seem to have any particular relationship with the elements listed above, but if you feel like bringing them out, nobody will judge you. Without going into too much detail, you will notice that the space (the place as a whole, what links or distances the pieces to each other, or to us) has been treated with consideration – this is an important aspect of the artist’s practice. For the rest, I like that his pieces always defeat what one might want to say about them. I think this is because they are relatively poor. To the fact that they are seen without any artifice, but perhaps not without modesty.

I don’t want to let my reading contaminate the end of this text, but it is obvious that in this balance, something upsets me.”

Franck Balland

Énergies Judith Hopf

22 September — 11 December 2022

Bétonsalon is partnering with Le Plateau, Frac Île-de-France to host a two-part exhibition by Judith Hopf.

Since the 2000s, the German artist has been making sculptures and films fuelled by her reflections on the relationships that human beings have with technology. For this first monographic exhibition in France, Judith Hopf unites existing and previously unseen works. Some of them resonate from one exhibition to the other. Its title, Énergies, refers to what fuels each of our everyday electrical appliances, viewed from both a technical and philosophical perspective.

While at Le Plateau, the works revolve around the transformation of the landscape into a source of energy, it is more a question of its consumption at Bétonsalon. A sculpture created for the exhibition represents a lightning bolt, a natural explosion that highlights the origin of electricity, its power and danger. Its use is at the heart of Énergies, where sculptures and films suggest a world dependent on electricity consumed without consideration for the terms of its production. We discover the Phone Users, human figures busy looking at their telephones. Absorbed in the contemplation of their screens, they seem cut o from their immediate environment, which is comprised of oversized apple peel sculptures.

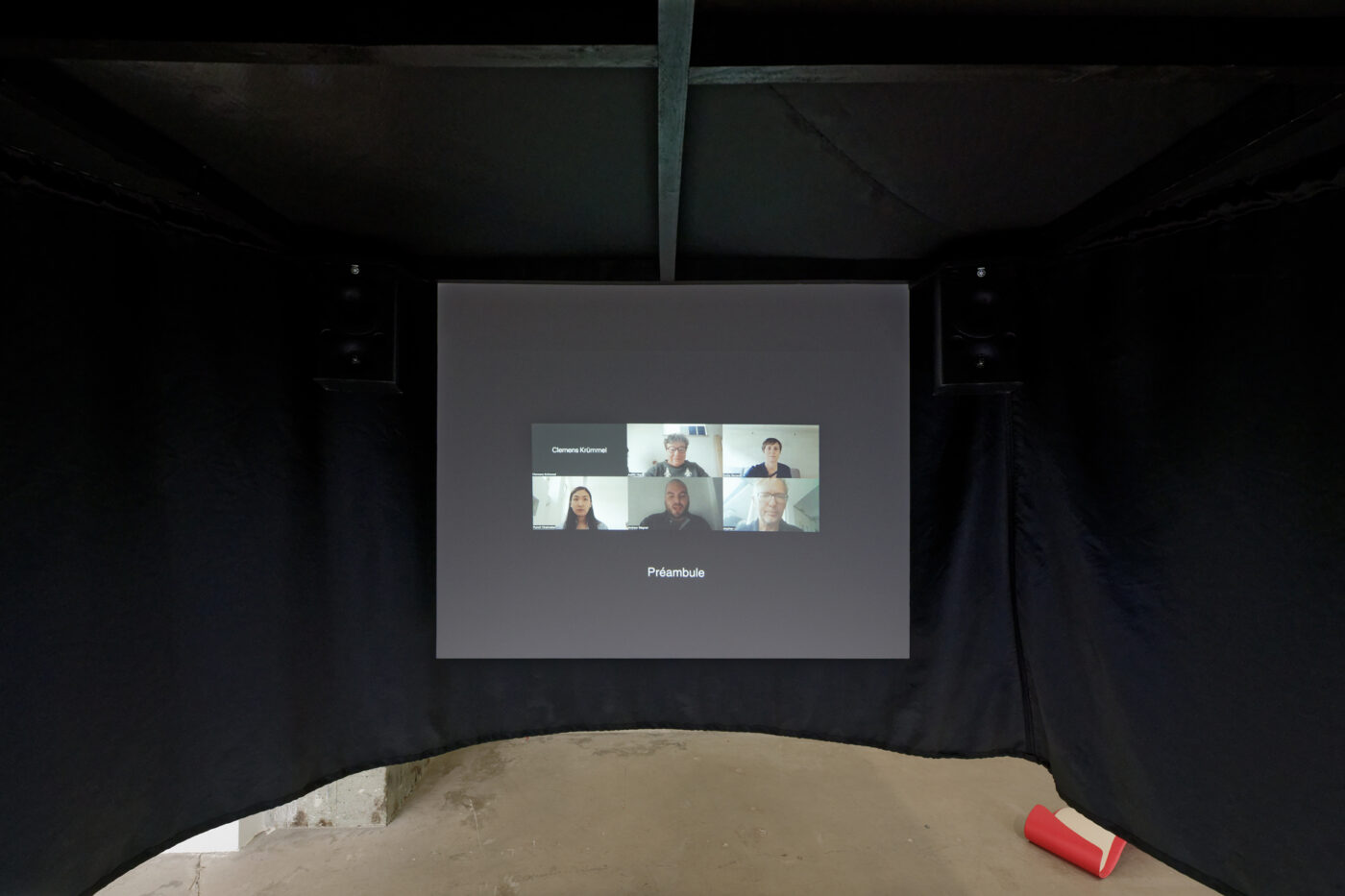

Judith Hopf’s work is full of the contradictions that pervade our daily lives and which she brings to light in all their strangeness. The numerous inversions and shifts that she brings into play in her work, by representing scenes that are so familiar that they become unusual, even ironic, are an invitation to think of alternatives, to see differently rather than to consume more and more quickly. Moreover, Énergies reminds us that in this age of videoconferencing, large quantities of electricity and human energy are needed to set up exhibitions. The Phone Users are a metaphor for this, presuming that they try to reach each other between the two exhibitions, and that they try to communicate to the extent of announcing to each other: “There’s no network”.

Off-site / Cette inondation-là, mais en mieux With Charlie Boisson, Marion Chaillou, Anna Reutinger, Phoebe Hadjimarkos-Clarke, Yasmine El Amri, Léa Rivière, Yoann Dumel-Vaillot

Exposition à Pauline Perplexe

3 December 2022 — 8 January 2023

3 December 2022 — 8 January 2023

In the courtyard of Pauline Perplexe, shut away and buried long enough ago for no-one alive to remember seeing it, flows the Bièvre. A local river that has become mythical, its lapping sounds cradled residents and craftspeople, irrigated vegetable gardens and powered mills for centuries, before it became too dirty and too smelly to be allowed to cohabit the landscape. This bucolic imagination has a silver lining: the Bièvre has become the emblem of a close, buried nature, which town councils undertake to bring out of the ground to green their districts. On the road that leads here, between the grassy embankments that have been filled in for the occasion along the main road, you can once again catch a glimpse of this little stream, which is as harmless as it is touching. In the case of Pauline Perplexe’s two houses, the Bièvre, swollen by rainwater, sometimes rises up to flood the basements: the proximity of a river sometimes means saltpetre and dampness rather than grass and freshness. But above all, once the damage is done, it’s a story that’s visual and funny enough to be told often, and to become part of the folklore of the place. That’s why I’m using it to introduce this exhibition, which combines artworks with texts and voices, based on flows, spurts and overflows. It has been built up by the association of ideas, in the same way that drops come together to form a puddle, if the metaphor had to be stretched.

Yasmine El Amri’s work is surely the most direct extension of this topographical and urbanistic interest in fresh water, its paths and diversions, its dividing lines and canals, which she puts into words and performances with a great deal of imagery and poetry. There is the “icy bubbling water” of the landscapes sketched out by Léa, whose name is La Rivière, in which the “geological lesbians” of her text armes molles bathe, telling us stories of communion, rituals and passages between beings, their bodies and landscapes, with great solemnity and no less humour.

If a flood can be surprising and frightening, there are also geysers that we are happy to let ourselves be drenched in, and it is often on this boundary that Charlie Boisson plays with his installations, where the enigmatic is a foil to fetishism, as here in La ronde des choses, which speaks of the reciprocal relationships between objects and symbols, and where the softness and sharpness of the materials cohabit in a low light.

But for the better? The title is borrowed from Tabor, a novel by Phoebe Hadjimarkos-Clarke, which opens with our world covered by water, and the survivors taking refuge on dry land plateaus, in camps where other models of community life are being tried out, and where Mona and Pauli continue their love story.

The mischievousness and melancholy of Marion Chaillou’s gouaches, whose format could be likened to illuminations or phylacteries, the non-eventfulness of her subjects and her poetic enumeration, remind me vividly of the atmosphere that reigns in the Tabor that appeared in my imagination as I read.

Finally, the Bièvre, with the tapestry factories of Gobelins and then Jouy, carries a long and dense history of know-how, secrets and colours, which Anna Reutinger’s project echoes, paying tribute to and documenting the peasant and artisan revolts of the late Middle Ages across Europe. We’re not talking here about scarlet, which made the waters of the Bièvre so prized by dyers, but rather madder, a plant known officially for its dyeing virtues and unofficially for its abortifacient properties.

And it’s this story that Yoann Dumel-Vaillot will use to close the exhibition: the outbursts and uprisings, the alchemy that works or doesn’t, and the unverifiable legends we love to believe.

Current

Upcoming